How to Do

Strategic Planning

How to Do Strategic Planning Like a Futurist

PAGEREF _Toc101804189 \h 1

Why We Avoid Long-Term Timelines

PAGEREF _Toc101804190 \h 3

Use Time Cones, Not Time Lines

PAGEREF _Toc101804191 \h 6

Imagining the Future for Golf Carts (or Mini-Gs)

PAGEREF _Toc101804192 \h 8

How to Do Strategic Planning Like a Futurist (pdf)

Chief strategy officers and those responsible for shaping the

direction of their organizations are often asked to facilitate

“visioning” meetings. This helps teams brainstorm ideas, but it

isn’t a substitute for critical thinking about the future. Neither

are the one-, three-, or five-year strategic plans that have become

a staple within most organizations, though they are useful for

addressing short-term operational goals. Futurists think about time

differently, and company strategists could learn from their

approach. For any given uncertainty about the future — whether

that’s risk, opportunity, or growth — we tend to think in the short-

and long-term simultaneously. To do this, consider using a framework

that doesn’t rely on linear timelines or simply mark the passage of

time as quarters or years. Instead, use a time cone that measures

certainty and charts actions.

I recently helped a large industrial manufacturing company with its

strategic planning process. With so much uncertainty surrounding

autonomous vehicles, 5G, robotics, global trade, and the oil

markets, the company’s senior leaders needed a set of guiding

objectives and strategies linking the company’s future to the

present day. Before our work began in earnest, executives had

already decided on a title for the initiative: Strategy 2030.

I was curious to know why they chose that specific year — 2030 — to

benchmark the work. After all, the forces affecting the company were

all on different timelines: Changes in global trade were immediate

concerns, while the field of robotics will have incremental

advancements, disappointments, and huge breakthroughs — sometimes

years apart. Had the executives chosen the year 2030 because of

something unique to the company happening 11 years from today?

The reason soon became clear. They’d arbitrarily picked the year

2030, a nice round number, because it gave them a sense of control

over an uncertain future. It also made for good communication.

“Strategy 2030” could be easily understood by employees, customers,

and competitors, and it would align with the company’s messaging

about their hopes for the future. Plus, when companies go through

their longer-term planning processes, they often create linear

timelines marked by years ending in either 0s or 5s. Your brain can

easily count in fives, while it takes a little extra work to count

in 4s or 6s.

Nice, linear timelines offer a certain amount of assurance: that

events can be preordained, chaos can be contained, and success can

be plotted and guaranteed. Of course, the real world we all inhabit

is a lot messier. Regulatory actions or natural disasters are wholly

outside of your control, while other factors — workforce

development, operations, new product ideas — are subject to layers

of decisions made throughout your organization. As all those

variables collide, they shape the horizon.

Chief strategy officers and those responsible for choosing the

direction of their organizations are often asked to facilitate

“visioning” meetings. This helps teams brainstorm ideas, but it

isn’t a substitute for critical thinking about the future. Neither

are the one-, three-, or five-year strategic plans that have become

a staple within most organizations, though they are useful for

addressing short-term operational goals. Deep uncertainty merits

deep questions, and the answers aren’t necessarily tied to a fixed

date in the future. Where do you want to have impact? What it will

take to achieve success? How will the organization evolve to meet

challenges on the horizon? These are the kinds of deep, foundational

questions that are best addressed with long-term planning.

i

As a quantitative futurist, my job is to investigate the future

using data-driven models. My observation is that leadership teams

get caught in a cycle of addressing long-term risk with rigid,

short-term solutions, and in the process they invite entropy. Teams

that rely on traditional linear timelines get caught in a cycle of

tactical responses to what feels like constant change being foisted

upon them from outside forces. Over time, those tactical responses —

which take significant internal alignment and effort — drain the

organization’s resources and make them vulnerable to disruption.

For example, in 2001 I led a meeting with some U.S. newspaper

executives to forecast the future of the news business. They, too,

had already settled on a target year: 2005. This was an industry

with visible disruption looming from the tech sector, where the pace

of change was staggeringly fast. I already knew the cognitive bias

in play (their desired year ended in a five). But I didn’t

anticipate the reluctance to plan beyond four years, which to the

executives felt like the far future. I was concerned that any

strategies we developed to confront future risk and find new

opportunities would be only tactical in nature. Tactical actions

without a vision of the longer-term future would result in less

control over how the whole media ecosystem evolved.

To illustrate this, I pointed the executives to a new Japanese i-Mode

phone I’d been using while living in Tokyo. The proto-smartphone was

connected to the internet, allowed me to make purchases, and,

importantly, had a camera. I asked what would happen as mobile

device components dropped in price — wouldn’t there be an explosion

in mobile content, digital advertising, and revenue-sharing business

models? Anyone would soon be able to post photos and videos to the

web, and there was an entire mobile gaming ecosystem on the verge of

being born.

Smartphones fell outside the scope of our 2005 timeline. While it

would be a while before they posed existential risk, there was still

time to build and test a long-term business model. Publishers were

accustomed to executing on quarter-to-quarter strategies and didn’t

see the value in planning for a smartphone market that was still

many years away.

Since that meeting, newspaper circulation has been on a steady

decline. American publishers repeatedly failed to do long-term

planning, which could have included radically different revenue

models for the digital age. Advertising revenue has fallen from $65

billion in 2000 to less than $19 billion industrywide in 2016. In

the U.S., 1,800 newspapers closed between 2004 and 2018. Publishers

made a series of short-term tactical responses (website redesigns,

mobile apps) without ever developing a clear vision for the

industry’s evolution. Similar stories have played out across other

sectors, including professional services, wired communications

carriers, savings and loan banks, and manufacturing.

i

Futurists think about time differently, and company strategists

could learn from their approach. For any given uncertainty about the

future — whether that’s risk, opportunity, or growth — we tend to

think in the short- and long-term simultaneously. To do this, I use

a framework that measures certainty and charts actions, rather than

simply marking the passage of time as quarters or years. That’s why

my timelines aren’t actually lines at all — they are cones.

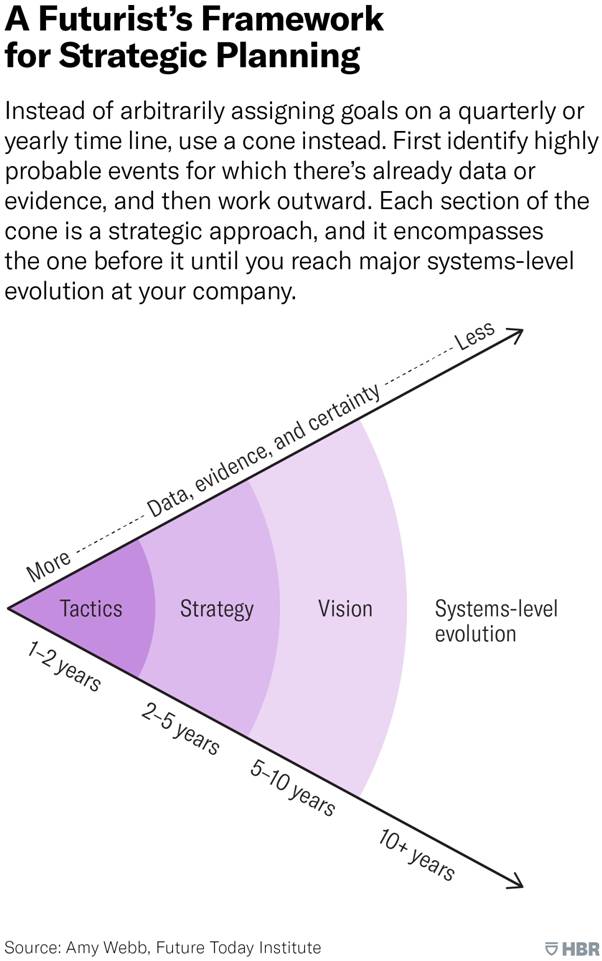

For every foresight project, I build a cone with four distinct

categories: (1) tactics, (2) strategy, (3) vision, and (4)

systems-level evolution.

I start by defining the cone’s edge, using highly probable events

for which there is already data or evidence. The amount of time

varies for every project, organization, and industry, but typically

12 to 24 months is a good place to start. Because we can identify

trends and probable events (both within a company and external to

it), the kind of planning that can be done is tactical in nature,

and the corresponding actions could include things like redesigning

products or identifying and targeting a new customer segment.

Tactical decisions must fit into an organization’s strategy. At this

point in the cone, we are a little less certain of outcomes, because

we’re looking at the next 24 months to five years. This area is

what’s most familiar to strategy officers and their teams: We’re

describing traditional strategy and the direction the organization

will take. Our actions include defining priorities, allocating

resources, and making any personnel changes needed.

Lots of organizations get stuck cycling between strategy and

tactics. While that process might feel like serious planning for the

future, it results in a perpetual cycle of trying to catch up: to

competitors, to new entrants, and to external sources of disruption.

That’s why you must be willing to accept more uncertainty as you

continually recalibrate your organization’s vision for the future. A

company’s vision cannot include every detail, because there are

still many unknowns. Leaders can articulate a strong vision for 10

to 15 years in the future while being open to iterating on the

strategy and tactics categories as they encounter new tech trends,

global events, social changes, and economic shifts. In the vision

category, we formulate actions based on how the executive leadership

will pursue research, where it will make investments, and how it

will develop the workforce it will someday need.

But the vision for an organization must also fit into the last

category: systems-level disruption that could unfold in the farther

future. If executive leaders do not have a strong sense of how their

industry must evolve to meet the challenges of new technology,

market forces, regulation, and the like, then someone else will be

in a position to dictate the terms of your future. The end of the

time horizons cone is very wide, since it can be impossible to

calculate the probability of these kinds of events happening. So the

actions taken should be describing the direction in which you hope

the organization and the industry will evolve.

Unlike a traditional timeline with rigid dates and check-ins, the

cone always moves forward. As you gain data and evidence and as you

make progress on your actions, the beginning of the cone and your

tactical category is always reset in the present day. The result,

ideally, is a flexible organization that is positioned to

continually iterate and respond to external developments.

i

For an example, let’s consider how a company that manufactures golf

carts could use this approach when considering the future of

transportation. We would consider some of the macro forces related

to golf carts, such as an expanding elderly population and climate

change. We’d also need to connect emerging tech trends that will

impact the future of the business, such as autonomous last-mile

logistics, computer vision, and AI in the cloud. And we would

investigate the work of startups and other companies: Amazon,

Google, and startups such as Nuro are all working on small vehicles

that can move packages short distances. What emerges is a future in

which golf carts are repurposed as climate-controlled delivery

vehicles capable of transporting people, medicine, groceries, office

supplies, and pets without a human driver. Let’s call them mini-Gs.

The golf cart manufacturer probably already has the core competency,

the supply chain, and the expertise in building fleets of vehicles,

giving it a strategic advantage over the big tech companies and

startups. This is an opportunity for a legacy company to take the

lead in shaping the evolution of its future.

With a sense of what the farther future might look like, leaders can

address the entire cone simultaneously. There will need to be new

regulations governing speed and driving routes. City planners and

architects will be useful collaborators in designing new entrance

ways and paths for mini-Gs. Drug stores like CVS and Walgreens could

be early buyers of mini-Gs; offering climate-controlled home

delivery of prescriptions could eventually lead to using mini-Gs to

collect blood or other diagnostic samples as the technology evolves.

Working at the end of the cone, the golf cart manufacturer’s leaders

will determine how the ecosystem forms while they simultaneously

develop a vision for what their organization will become.

Working at the front of the cone, executives will incorporate

mini-Gs into their strategy. The actions here will take deeper work

and more time: setting and recalibrating budgets, reorganizing

business units, making new hires, seeking out partners, and so on.

They will build in flexibility to make new choices as events unfold

over the next three to five years. While the mini-Gs future I

described above may still be very far off, this will position the

company to pursue tactical research today: on the macro forces

related to golf carts, emerging tech trends, and all of the

companies, startups, and R&D labs currently working on various

components of the ecosystem, such as last-mile logistics and object

recognition. Over the next year, the golf cart manufacturer will

bring together a cross-functional team of employees and experts;

perform an internal audit of capabilities; facilitate learning

sessions and workshops; assess current and potential vendors; and

stay abreast of new developments coming from unusual places. What

employees and their teams learn from taking tactical actions will be

used to inform strategy, which will continually shape the vision of

the company and will position it to lead the golf cart industry into

the future.

Dozens of organizations around the world use the time horizons cone

in the face of deep uncertainty. Because their leaders are thinking

exponentially and taking ongoing incremental actions, they are in

position to shape their futures. It might go against your biological

wiring, but give yourself and your team the opportunity to think

about the short- and long-term simultaneously. Resist the urge to

pick a year ending in a 0 or 5 to start your strategic planning

process. You will undoubtedly find that your organization becomes

more resilient in the wake of ongoing disruption.

i

Amy Webb

is a quantitative futurist and professor of strategic foresight at

the New York University Stern School of Business.

About TACS

|

TACS Science

Technology Engineering and Consulting Delivers The Insight and Vision on Information

Communication and Energy Technologies for Strategic Decisions.

TACS is Pioneer and Innovator of many Communication Signal

Processors, Optical Modems, Optimum or Robust Multi-User or

Single-User MIMO Packet Radio Modems, 1G Modems, 2G Modems, 3G

Modems, 4G Modems, 5G Modems, 6G Modems, Satellite Modems, PSTN

Modems, Cable Modems, PLC Modems, IoT Modems and more..

TACS scientists engineers and consultants conducted fundamental scientific research in

the field of communications and are the pioneer and first

inventors of PLC MODEMS, Optimum or Robust Multi-User or

Single-User MIMO fixed or mobile packet radio structures in the

world.

TACS is a leading concept technology provider and top

science technology engineering and consultancy in the field of Information,

Communication and Energy Technologies (ICET). The heart of our

Consulting spectrum comprises strategic, organizational, and

technology-intensive tasks that arise from the use of new

information and telecommunications technologies. TACS Science

Technology Engineering and Consulting

offers Strategic Planning, Information, Communications and

Energy Technology Standards and Architecture Assessment, Systems

Engineering, Planning, and Resource Optimization.

|

TACS is a leading top consultancy in the field of information, communication

and energy technologies (ICET).

The heart of our consulting spectrum comprises strategic,

organizational, and technology-intensive tasks that arise from the use of new

information, communication and energy technologies.

The major emphasis in our work is found in innovative consulting and

implementation solutions which result from the use of modern information,

communication and energy technologies.

TACS

- Delivers the insight and vision

on technology for strategic decisions

- Drives

innovations forward as part of our service offerings to customers

worldwide

- Conceives

integral solutions on the basis of our integrated business and technological

competence in the ICET sector

- Assesses technologies and standards and develops

architectures for fixed or mobile, wired or wireless communications systems

and networks

- Provides

the energy and experience of world-wide leading innovators and experts in their fields for local,

national or large-scale international projects.

|